- Home

- Paula Houseman

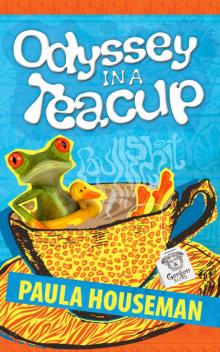

Odyssey In A Teacup

Odyssey In A Teacup Read online

ODYSSEY IN A TEACUP

Paula Houseman

Amazon Kindle Edition

Title: Odyssey in a Teacup

Author: Paula Houseman

Publisher: WildWoman Publishing

Sydney, Australia

Amazon Kindle Publishing Consultant: Lama Jabr

Sydney, Australia

Copyright © 2015 Paula Houseman, WildWoman Publishing.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Connect with Paula Houseman

Website: http://paulahouseman.com

Social Networks

https://www.linkedin.com/pub/paula-houseman/17/89/320

https://www.pinterest.com/paulahouseman

https://twitter.com/paulahouseman

DEDICATION

For Kelly and Jared

CONTENTS

Part One: In Hot Water

Chapter One: Family Jewels

Chapter Two: Fourplay

Chapter Three: Dates & Lemons

Chapter Four: Not with a Bang but a Whimper

Chapter Five: Her Big Fat Jewish Wedding

Chapter Six: Fruity Nuts

Chapter Seven: Lights on, Nobody Home

Chapter Eight: Warts ‘n’ All

Chapter Nine: Wind Beneath My Minge

Chapter Ten: An Ill Wind Sucks

Chapter Eleven: Escape from the Mad House

Chapter Twelve: Ship of Fools

Chapter Thirteen: Wedding Daze

Chapter Fourteen: Real Estate Low-down

Chapter Fifteen: Kiddie Litter

Part Two: Tea and Sympathy

Chapter Sixteen: Casual Chic

Chapter Seventeen: Doctoring

Chapter Eighteen: Dropping(s)

Chapter Nineteen: Latest Crazed

Chapter Twenty: Fashion Flops

Chapter Twenty-One: Inside Jobs

Chapter Twenty-Two: Pieces of Work

Chapter Twenty-Three: There’s the Rub

Chapter Twenty-Four: Up-endings

PART ONE:

IN HOT WATER

CHAPTER ONE:

FAMILY JEWELS

‘Hello, I’m Ruth Roth,’ I said to my bedroom mirror when I was five. I talked to it often, always starting with hello because my generation was brought up with manners ... or effective social conditioning, anyway.

This time, it replied with a bitchy reminder. ‘Yes, but you’re just Ruth. Not Ruth Michelle, nor Ruth Katherine. No middle name; one syllable. Not like Myron.’

Eleven months older than me, my brother My-ron Ste-phen Law-rence Roth got two middle names and six syllables. Even to my five-year-old sensibilities, the difference in naming reeked of injustice, so I whined through my gappy milk teeth to our father, Joe (Jo-seph Ben-ja-min Roth).

‘It’th not fair! Why did Myron get two middle name’th and I got none?’

‘Because the extra initials will look good printed in his cheque book.’

What fucking checked book? He’s only six years old! Oh, I knew these things were adult books, but still, fair’s fair. ‘I want a checked book too!’

‘Girls don’t need one.’

And there it was. Four bloody words that set a precedent for my standing in the family, and beyond. Then Syl-vi-a Es-ther Roth, our mother, put in her two cents’ worth, not only sealing the deal, but supergluing it, further contributing to my thorny relationship with mirrors.

‘Oeuf! What difference does it make? Pest!’

Our parents were born in Egypt of European ancestry. They are multilingual but mainly speak to each other in French. Oeuf means egg. Others might preface an irritated response with ‘Shit!’ Or ‘Godammit, child!’ But not Sylvia. I never questioned this as I assumed it was the norm, just like her use of pest. This word often closed a sentence, kind of like ‘Amen’ at the end of a prayer or creed. If it is so and so be it, then what’s to question? Pest thus became a metonym for Ruth.

My feelings about being a nuisance not worthy of a middle name grew legs on my first day in Grade 1, when the teacher, Mrs Taylor, called the roll:

‘Rivers, Susan Marie.’

‘Present,’ said Susan Marie Rivers.

‘Roberts, Paul Malcolm.’

‘Present,’ said Paul Malcolm Roberts.

Mrs Taylor paused for a bit before she said, ‘Roth, Ruth.’

‘Present.’

She paused again. ‘Don’t you have a middle name?’

‘No.’

‘Oh.’ She said it like it was something bad. The rest of the class must have thought so too because they sniggered.

I often fantasised about what it would be like to have a different name, an extra one, or even some extra syllables. It wasn’t like it was a big ask. And as we students mastered the vowels in the early years, I got my wish. Sort of. Shaun Farr, a very clever boy in my class, came up with the nickname, Rath-Reth-Rith-Roth-Ruth. That the other kids could even be bothered saying it whenever they spoke to me filled me with a sense of importance. Still, the name Ruth, in and of itself, brought its own problems.

My well-meaning, heavily accented Yugoslav, lots-of-syllables aunt, Miroslava (Miri), pronounced ‘th’ as ‘t’. So to her, I was ‘Root’.

‘Hullaw, Root. How arrr yoo, Root? Vot did yoo doo et school dis veek, Root?’

Joe was dirty-minded and foul-mouthed, so from an early age, I knew that a root wasn’t just the underground part of a plant. My older cousins knew it too, and because we had to spend every Sunday with the relatives, I was well and truly ‘rooted’ by early adolescence. It was only then that it became clear there was a need to stand my ground with Sylvia.

‘I AM NOT SEEING THESE PEOPLE ON SUNDAYS ANYMORE, YOU CAN’T MAKE ME!’

‘DON’T YOU DARE YELL AT ME!’

‘You yell at me!’

‘Oeuf! I’M YOUR MOTHER, I’M ALLOWED! And this is not a democracy; you’ll do as you’re told. Pest!’

That she demonstrated a political bent was pretty impressive; that she got her way was an outrage. But even when I was old enough to exercise my civil liberties, I couldn’t escape my name, and yet another challenge that came with it.

The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, a movie released in 1972, popularised the expression to ‘cry Ruth’, meaning ‘to vomit’. To ‘cry Ruth’ became a national catchphrase. Friends, relatives and acquaintances fake hurled around me ad nauseam. It was awful at first, but then—in a perverse kind of way—I rejoiced in it. Being Ruth made me the centre of attention. Only one name with only one syllable but by God, I was one of the cool people! At least until the saying lost currency and I was once again uncool. Even knowing I had the same name as a biblical heroine didn’t appease me.

‘Oeuf! You’re never satisfied, pest!’

I might have been satisfied if I didn’t feel like a gatecrasher. Sylvia had fallen pregnant with me when Myron was only two months old. It was not exactly a dream come true. No woman in her right mind would want to get pregnant on the back of giving birth. It makes sense then that I was accidental, not incidental, but they (she and Joe) told me I was a ‘mistake’. Big difference between an accident and a mistake. Huge one! That label—feeling unwanted

—was so unfair because even though there had been a nine-month gestational war between Sylvia and me, I slipped out of her vagina quickly and smoothly, rather like the soldiers slunk out of the Trojan Horse. Sylvia had conveniently forgotten her epic labour with Myron and she forgave him for the nasty perineal tears he’d caused, probably because he toed the line thereafter, where I was always stepping on it and over it.

Myron the sycophant was their jewel in the crown, invested with their hopes and dreams. I was the misfit, like the ugly duckling who ended up in the wrong family. I’m not ugly, though; Joe often told me I’d get by because of my looks. But he never said anything about substance. And just like in the story, being different, especially in the fifties and sixties, translated to ugly. Or invisible.

If you could have seen me back then, you’d have noticed the difference in appearance between them and me. And that hasn’t changed. Sylvia, Joe and Myron are tall, pale-skinned and blue-eyed. Sylvia and Myron have thick, blond hair; Joe’s hair—most of which he lost in his twenties—is thin and Grecian Formula brown. All three of them are double-chinned butterballs with appetites like Jabba the Hutt, and the same sluggish metabolism. If I were visible back then, it would have surprised you to know that my appetite could match theirs and Jabba’s (seems my thyroid works much more efficiently). If I were visible, you’d have seen the smallish, oval face, the large hazel eyes, olive skin, and reddish, mid-brown hair—not straight, not curly, but with a definite kick in it, parted on the left and extending a couple of inches below my shoulders. And you would also have noticed the high waist and long legs, giving the impression of height. But this was an illusion. Even as an adult, I’m a short-arse, a neat sixty-three and a half inch package. Convert me to a one hundred and sixty-one-centimetre package, if you prefer. In fact, when a desire to fit in took hold, I’d often lapse into everyman’s land, and could be converted into practically anything you wanted me to be. It all started with this:

‘Oeuf! Why can’t you be like everyone else? Pest!’

Tried that on for size; didn’t like it. Nor did she, it seemed:

‘Oeuf! Why do you have to be like everyone else? Pest!’

Despite Sylvia’s browbeating, I was never quite the right fit for her, and her hectoring could be dispiriting. She used to tell me that if I felt intimidated by a schoolteacher, I should imagine them on the toilet. I imagined her on the crapper one night just after we sat down for dinner and she started nagging. It didn’t work. Then, an image came to mind quite unexpectedly: an old blonde mare whinnying—nei-ei-ei-ei-eigh, oe-oe-oe-oeuf, nei-ei-ei-ei-eigh—snorting, baring its big pink gums and big yellow teeth, massive lips retracted and flapping away through the nickering. Now this worked for me. But it backfired because I started laughing. Sylvia reared up on her hindquarters and slapped me down.

Living with this woman was punishing. Luckily, I had an ally close by in my cousin, Ralph Brill (single syllable, no middle name; he didn’t give a shit). Also an outsider in his family, Ralph and I were best friends, kindred spirits. We were separated by only one week (I was first), but inseparable and in sync (one of our many commonalities was our names; ‘to ralph’ is American slang for ‘to vomit’). He and I bonded as infants from the moment we could see a world beyond our own feet and hands.

Unsurprisingly, as a baby I only ever commando crawled. Ralph, on the other hand, bear crawled on his hands and feet like a chimp or ... a bear. Our mothers often got together, and when Ralph and I grew tired of our quadrupedalling and slithering around the floor, we could be found asleep in a corner with our arms around each other. Like twins. They thought it was so cute. Later on, though, the fact that Ralph and I didn’t see the world through the eyes of our nearest and dearest was not considered so cute. We were soon labelled the black sheep of our respective families.

Ralph and I had each other’s back and our rare arguments were over minor things, although we did come to blows over a serious issue when we were five and a half. Ralph helped himself to some of my ice cream—and I lost it! I would give my cousin the ruffled, broderie anglaise shirt off my back, but not my bloody ice cream. I yelled at him, called him Ralph Shitface Brill! He cried, but then he hit back. ‘Well at least now I’ve got a middle name! Na-nana-naa-nah!’ I cried. Geez, who knew boys could be so bitchy?

Ralph’s mother, Norma, is my mother’s older sister. Unlike Sylvia, Auntie Norma is short and has wispy brown hair. But like Sylvia, she’s ‘well-upholstered’; although, Sylvia never considered herself fat: ‘The doctor told me I’m fleshy.’ She shared this fact with Myron and me when I was eight and I was learning about synonyms at school.

‘Fleshy is just a synonym for fat,’ I informed her. I didn’t know about political correctness back then, and I didn’t witness a whole lot of tact demonstrated at home. I got sent to my room.

Norma is married to Albie. Of German descent, Albie has pug-like features, is short, pasty-faced and bald (or maybe that should that be aesthetically disadvantaged, vertically challenged, Caucasoid, and follicularly impaired). He used to be fairly solid, but now he’s just plain ... fleshy. And like Porky Pig, Albie has a rampant st-t-t-tut-t-t-ter.

Where Norma’s a kind soul, Albie is eine widerliche Scheiße (an odious turd). He’s a brute, and for a long time Ralph was his whipping boy. Ralph’s mental acuity was his sword; albeit one that had a bit of a double edge. When Albie ripped into him with a stuttered string of invective, Ralph matched and mocked with a stuttered response. Not a great idea when you know the aggressor will retaliate with a ‘stuttered’ physical comeback: thwack-thwack-thwack.

Ralph is one of three boys. His two brothers also bullied him. Respectively six and three years older than Ralph, george and simon only deserve lower case initials befitting those with a Napoleon complex (Albie also suffers from small man syndrome, but he’s an Arschloch [arsehole] with a capital A). Still, Ralph staunchly and compassionately defended his brothers: ‘They’re only aggressive because they’ve got such über-small penises.’

And then there’s Louise. Three years younger than Ralph, she was a welcome ‘surprise’, not a mistake. Even so, she constantly whined (and still does). Ralph nicknamed his sister ‘Louwhiney’ from the time she started mewling.

As children, george and simon were stubby like their father and looked like pit bulls, and Louwhiney was a bit of a porker like Norma. But Ralph was the runt of the litter. He was the proverbial ugly duckling. Short and skinny, he had disproportionately huge teeth in a tiny, pale face, which was hidden behind thick, black-rimmed coke-bottle glasses (to correct a lazy eye). With his magnified eyes and his fine, mid-brown hair sticking out all over the place, he looked like a novelty Tweety Bird toilet brush. Ralph was also bookish, in contrast to his rugged and sporty brothers. That he could outfox them and his father with his smarts pissed them off no end. And bullies will stop short at nothing to get the upper hand.

When we were six, Albie’s brother, Kevin, gave Ralph a duckling as a pet. On the Sunday family gatherings at Ralph’s place, he’d put a little string around Daffy’s neck, and he and I would take the duck for a walk up and down the street. On Ralph’s seventh birthday, when he came home from school and went to feed Daffy, he couldn’t find him. Ralph wasn’t too worried because Daff always showed up sooner or later. And that he did. At dinnertime. Plucked. Roasted. À l’orange. Happy Birthday.

Of course, this was Albie’s idea. Ralph was inconsolable.

‘L-l-let the b-b-b-boy have one of the d-d-drumsticks, Norma,’ Alfie barked. It was a supposedly magnanimous gesture.

Nice going, Dummkopf!

That night, Ralph went to bed emotionally exhausted and on an empty stomach.

He was a real trouper, and rarely complained about his lot. My family was equally dysfunctional, but where we were on easy street, Ralph’s parents had trouble making ends meet. We went on holidays to far-flung locations; Ralph’s family stayed close to home. Myron and I always got brand new clothes; Ralph got hand-me-downs—underp

ants included—from his Uncle Kevin’s son, Gavin (simon inherited george’s clothes but they were always too worn to pass on to Ralph). Cousin Gavin is only a year older than Ralph but about four sizes larger, so his clothes swam on Ralph. Today, it might look super cool to have the crack of your arse showing above your too loose, too low-slung jeans, but back then, it was kind of tragic. And we always heard the whispers—what a nebbish (poor thing)—amongst the relatives at our Sunday get-togethers.

The venue for these torturous gatherings rotated on a weekly basis: Ralph’s place, our place, Uncle Isaac’s. Isaac, Norma and Sylvia’s brother, is married to Miri. Polite and reserved, Isaac is five years older than Sylvia, and two years younger than Norma. He and Sylvia are similar looking, with their height, blond hair and blue eyes, but Isaac is fairly trim. Miri is typically Slavic in appearance, with a wide forehead, round face, and high cheekbones. She’s short and rotund, and has dark brown hair. Isaac and Miri have three daughters—Mary, Betty and Zelda. Mary is the same age as george, Betty is the same age as simon, and Zelda is the same age as Louwhiney. The two older girls resemble their father in looks and build, but Zelda is built like Shamu, only with an attractive face (like Miri’s).

On the Sunday gatherings at my home, my two best girlfriends, Maxine Mayer-Rose and Yvette Klein (Maxi and Vette), would join us. The kids hung out in the backyard and if it rained, we played board games, marbles or charades on the large front verandah, which was undercover. The adults usually huddled in the lounge, smoking, the women gossiping and the men telling jokes. Notwithstanding the different nationalities, they’re all Jewish and except for Albie, they all speak Yiddish. When the gossip was a little too scandalous or the jokes a little too risqué, they switched from English to Yiddish, which we kids didn’t understand. Because Yiddish and German sound similar, Albie could understand, and be understood.

Odyssey In A Teacup

Odyssey In A Teacup