- Home

- Paula Houseman

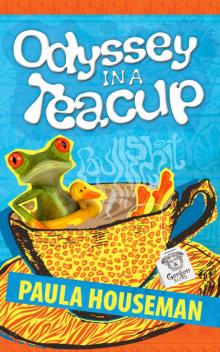

Odyssey In A Teacup Page 10

Odyssey In A Teacup Read online

Page 10

Although the evening might have seemed like a waste of time, I gained a lot from it. Had I broadened my spiritual horizons? I’d say so. But there was still a bit of a question mark over whether or not God had shown up. Back then, I expected Him to make a grand entrance. Not so much like Kishma’s stage entrance, more like a thunderbolt, razzle-dazzle appearance. A bit like when Ralph materialised in his silver lamé suit at Zelda’s wedding. Though I still thought of God as a person—a man—I’d figured out that Joe wasn’t Him. But I didn’t yet fully understand that The Dude expressed Himself cryptically and in many forms, such as through me every time I squared up to someone who attacked me. I did understand, though, that I didn’t need Maxi’s moxie, or Ralph’s. I had my own brand of it, and three dollars fifty was a small price to pay to resuscitate it. Now you see me.

Being a black sheep wasn’t so bad after all. And Kishma could kish ma ken tookhus.

CHAPTER EIGHT:

WARTS ‘N’ ALL

How far away is the horizon? It doesn’t matter as long as you can see it. Fog and scattered light can limit its visibility, but you’ve seen it often enough to at least know it still exists. Even though I’d broadened my spiritual horizons that night at the community hall, over the next few years, the fog of war in my head—me versus a militia of little Sylvias—escalated and increasingly made the horizon’s visibility poor. Eventually, I would stop looking, and worse, I would stop believing.

The meditation intro night might have brought me closer to the horizontal plane where the sky and the ocean meet, but time and again after that, I was likely to be found below the plane, partially submerged. Still, with an ever-present threat of being dragged down by the undertow, I furiously trod water. At times, Ralph also tired of the struggle to shine. In spite of his home environment, though, he couldn’t be held down for long.

Shortly after that woo-woo night, Ralph and I turned twenty-one. Sylvia and Joe had suggested a combined party, but I wasn’t in the right frame of mind, and Ralph had taken to downplaying his birthday (he’d never fully recovered from his seventh birthday celebration—‘I could have handled it if they’d served up Louwhiney on a platter with an apple in her mouth, but not my duck!’). Sylvia wanted to throw us a big bash.

‘And all the cousins will be there.’

What! That’s supposed to be the carrot? Are you kidding? ‘Um, no thanks.’

‘Oeuf!’

Sylvia offered to hold a twenty-first party for the next three birthdays. Each time, I declined; she oeufed. Then, just before I turned twenty-five, she threw her hands up in despair, and then tried another tack.

‘What do you want, pest?’

As Ralph, Maxi, Vette and I had got on with our respective lives, we didn’t see each other as often as we would have liked. But we each knew that if anything could revivify our spirits, it was precious time spent together. Maxi and Vette also had their challenges and needed to recharge as much as Ralph and I did. So, I bit the bullet.

‘I wouldn’t mind if you paid for a holiday away for me, Ralph, Maxi and Vette. You know, with whatever you were going to spend on the party.’

I’d done some research and calculated that what she and Joe had been prepared to outlay would cover the cost of four airline tickets to Surfers Paradise, and two nights’ accommodation at a beachfront hotel (two rooms). I told her so.

‘Okay.’

Whoa! That was easy. ‘Thank you!’

‘But we’re not paying for the putana!’

Of course not. Always some caveat. I shared the news with Ralph, Maxi and Vette, and the four of us were excited about our impending sojourn. Maxi was also understandably riled.

‘Christ! It was eight years ago that I posed. When is she gonna let up?’

‘Never. She’ll take that one to her grave.’

That was Sylvia. But we intended to have fun, even if Maxi had to pay her own way.

The weather when we arrived late Saturday morning was groovy. The hotel and our rooms were groovy. And we all felt ... groovy. Each room had two single beds. Ralph and I shared one room, and Maxi and Vette shared the other. Although I’d reconnected with Reuben and we’d gone out a few times, none of us were in serious relationships, so we could let our hair down. And that night, we did—band-watching, dancing and drinking at the Playroom Nite Club. We planned to spend the next day, my birthday, relaxing around the pool.

At breakfast, Ralph, Maxi and Vette surprised me with my gift. They’d all pitched in and booked me in for a mid-morning massage at the hotel. I was excited; it would be my first ever massage. And at five to ten, I left them lounging poolside and took off for an hour’s worth of bliss.

The tall, tawny-haired girl manning the corner reception desk of the hotel’s small health and fitness centre was expecting me. Her left breast was called April (the nametag said so). Was her right one called May?

‘Good morning!’ April’s owner was a chirpy one.

‘Hi. I’m booked in for a massage. Ruth Roth.’

‘Yes. Happy twenty-first birthday!’

‘Thank you. Actually, I’m twenty-five. It’s a belated present.’

‘Well ... better late than never!’

I thought of Sylvia. I think of Sylvia every time I hear a cliché. I wanted to get away from Sylvia, but here was her shadow, like an eclipse on the horizon.

‘So, how are you this morning? Are you enjoying your stay?’

‘I’m well, and yes I am, thanks.’

April then introduced me to Cheryl. ‘So, how are you this morning? Are you enjoying your stay?’ Cheryl asked as she escorted me past a small gym and to the massage studio.

I was still well, thanks and yes, I was still enjoying my stay. Thanks. Cheryl opened a squeaky door to an airy room, softly lit and very pink. Shag carpet, walls, cabinets, massage table, the folded towel on the massage table—all various shades of pink.

‘Just strip down to your underpants, no bra, lie face down on the massage table, and cover yourself with that little towel. The masseuse won’t be long.’

As instructed, I undressed, climbed onto the table and wrestled with the towel as I tried to pull it up over me and flip onto my stomach at the same time. I lay there for about a minute staring through the headrest hole at the table’s cold metal legs, and then I heard the door squeak open and close. I was now staring at a pair of feet in white (not pink) Dr Scholl’s leather clogs. They had rows of equidistant holes in them, probably a good thing if you’ve got a sweaty feet condition.

‘Good morning, my name’s Dee.’

That’s not a name; that’s a cup size.

‘How are you this morning? Are you enjoying your stay?’

Jesus! It’s happened. I’m officially in Stepford!

‘Good, thanks and yes, thanks.’

‘That’s the way!’ Dee had a sing-song, nasally voice. ‘I’m going to oil you up in a just a minute.’

And the door? The door could do with a little oil.

Dee continued talking right over my thoughts, ‘I’ll pop on some relaxing music and we can get started.’

Clack-clack-clack—the familiar sound of riffling through a stack of audiocassettes. But it was a rhythmic sound, so they were obviously neatly arranged, and not just thrown haphazardly into a box. A good sign of someone who works methodically. Thirty seconds later, the cries of an orca burst out from the speakers.

‘How’s that? Okay with you?’

Hell no, and it wouldn’t be okay with Greenpeace either! ‘Ooh, it’s a wee bit unsettling.’

A brief silence. Some more clacking.

‘This better?’ she asked over the sound of harps and running water.

‘Umm ... that’s a bit wee unsettling.’

Maybe Dee got the play on words. Maybe she didn’t. Either way, it seemed she was unimpressed. Her silence now was a heavy one, and the clacking got loud and impatient. I heard her thought transference: what a pain in the arse this one is. I felt ashamed, and one of Sylvia’s ritualised chants echoed

in my head: ‘You’re a difficult child!’ But the roar of a waterfall, like a thunderclap, suddenly and frighteningly filled the room and drowned out both transference and mantra, and brought to the surface a genuine fear of death by drowning. And not just my spirit drowning. This time I would have to be resurrected, which means coming back into a new body. Shit. What if I came back into one like Zelda’s? I started hyperventilating. Dee noticed this and must have softened because I felt her hand on my back.

‘Just slow your breathing down.’ Her voice was comforting. ‘Obviously this one’s not for you either.’

More clacking.

‘Is this one better?’ she asked wearily. Birds cheep-cheeped, wolves howled, possums revved like a malfunctioning chainsaw, owls hoo-hoo-hooed, frogs ribbited—get off my llllily pad!—and sitars and flutes played along with them all.

Your taste in music is crap. ‘Yes, that’s fine.’

We were not off to a good start; Dee and I weren’t exactly harmonising. And it was about to get a whole lot worse.

I tried to tune out the forest babble, and focused instead on the squishy sound of oil being rubbed between her hands. Any reservations I’d had started to dissolve slowly with her long, powerful strokes along my back. And Dee did work methodically. She manipulated the lower region—calves and thighs—then softly, but firmly, kneaded her way north towards the shoulders. At times, it felt like she was using a small loofah. Because I’d never had a massage before, I assumed she was using some sort of exfoliating tool. I was reluctant to ask, though, because I didn’t want to aggravate her again. I wanted her to think well of me, so I allowed myself to slip into a dreamlike state. Dee’s magical hands moved down my left arm, circling the elbow once, twice. Her nimble fingers slid towards my palm and beyond, locating pinkie, then ringman, then tallman, and then … fuck! She was working pointer, and that tool was no loofah. It was a wart ... on her thumbkin!

Slowing down my breathing this time wasn’t worth diddly-squat, as my mind hurtled back into the past and dredged up a distressing memory:

Primary school days, Adelaide. Grade two. His name was Dieter Baumschlager, an Austrian boy whose mother sent him to school every day in pale blue, knitted, goolie-hugging lederhosen. And as if that wasn’t bad enough, Dieter Baumschlager had warts. No other kid in the class had been issued with them because he had them all! Three or four per finger, like free-living barnacles attached to his extremities and feeding off them (he must have started masturbating when he was a preschooler).

I remembered a particular incident quite clearly suspended in time. A school excursion, my class walking down Rowells Road. Mrs Russo, the teacher accompanying us, instructed us all to hold hands. The girls standing near Dieter baulked and deftly moved away, leaving me the one closest to him. Mrs Russo stared at me. I didn’t budge. Mrs Russo now gave me a dirty, filthy look (like Sylvia often did). I felt ashamed but was not prepared to buckle under the intensity of her disapproval.

If I was unlucky enough to get paired with Dieter on the days we had folk dancing at school, I managed to avoid holding his hand because I’d grab his shirt cuff, or his wrist if he was wearing a short-sleeved shirt. There were always too many children in the yard for the teachers to notice. But this was a summer’s day and I was cornered. Still, I stared right back at Mrs Russo and defiantly folded my arms. She started tapping her foot (like Sylvia often did).

‘I said, hold hands!’ There was a menacing tone in her voice.

Only when Hell freezes over.

With all the courage a seven-year-old could muster, and now with arms akimbo, I refused point blank. I stood my ground. By God, I had moxie back then!

‘You’re a difficult child!’ said Mrs Russo. With that, she had found my Achilles heel (I had two feet, so I could have had two Achilles heels). She won. Shaken, I let Dieter take my hand. I was acutely aware of every little scratchy lump on his fingers. The experience traumatised me, and another phobia manifested: dermatosiophobia (fear of skin diseases and warts).

I was jolted back into the overdone pink present. Dee’s diseased thumb was now moving back up my arm, across my shoulders, and down towards my right hand. The outcrop seemed to have grown exponentially. I was being steamrolled by a wart and I was pissed! You should never have to pay to contract a virus, or even get one as a present! And if I’d celebrated my twenty-first birthday on my twenty-first or my twenty-second, twenty-third, twenty-fourth, or even my twenty-sixth birthday, this wouldn’t be happening because none of these fell on a bloody Sunday!

I nosedived into another chilling flashback, fast-forward one year from that school excursion:

After that terrible day, I kept my distance from Dieter Baumschlager at all costs. But all those creative manoeuvres to avoid him had come to naught on the day I discovered three warts on the underside of my feet.

‘Verrucas!’ proclaimed Dr McGinty. Didn’t know what it meant, didn’t care. Verrucas weren’t warts, right? Dieter Baumschlager had warts. I had verrucas. Besides, they were on my feet, not my fingers. Dieter never touched my feet and I knew about hygiene. I used to scrub my hands with lots of soap and water straight after any contact with him. And there was no connection between my feet and my fingers, right?

‘Verrucas are warts on the sole of the foot, Ruth,’ Dr McGinty explained, kindly. ‘And yes, there is a connection. You know that song, “Dem Bones”?’ He was talking to me like I was an idiot. Sylvia laughed and the two of them broke into song—each one taking turns to sing and botch every line of it.

‘The toe bones join up with the metatarsals that connect with the ankle ones ... ’ ♬

‘And then they connect with the thigh bones ... ’

‘The femur attaches to the rib bones ... ’

‘The rib bones connecting to the head bone ... ’

‘The cranial bones connect with the scapula, that connects with the ulna, and that then connects with the finger bones ...’ ♬

Her cock-ups I could understand, but how the hell did he become a doctor if he couldn’t understand basic anatomy? They laughed heartily when they finished. If what they’d said (or sung) was right (even as it was all wrong), then it had taken one year from the point of contact—Baumschlager’s and my fingers—for the warts to work their way down through the network of bones to reach my feet. But what they’d said (or sung) was bullshit, because the spread of a virus has nothing to do with the way bones connect. An eight-year-old doesn’t know that, though. Surely, a forty-something doctor should. Who’s the idiot, then? He now took a serious tone:

‘She needs to soak the affected parts in a preparation of salicylic acid.’

I had a vision of the flesh of the sole eaten away by the solution, eventually exposing the metatarsals. I was crushed, overcome with a devastating sense of loss at the prospect of never being able to wear red jelly sandals.

‘ARE YOU OKAY?’ Dee was bellowing.

I felt disoriented. It took a while to register where I was. Caught between past and present, mouth dry with fear, I was hyperventilating again and sweating profusely.

‘Actually, I’m a little queasy. Are you nearly done?’

‘I think we can finish up now. Would you like a glass of water?’

What? Wart-a? Shit! I was in a wart-centred state of mind, connected to it like dem bloody bones. Any attempt to disconnect was ... thwarted. See!

‘Er, yes please.’

I sat up. She handed me a half-full glass as I gave her a glass half-full silent appraisal: disfigurement aside, Dee was a pretty redhead. Twenty-something, diminutive but relatively busty (probably a Dee-cup), nipples straining like a pair of peas against her tight, monogrammed T-shirt.

So that’s what the flake looks like, she transmitted, but asked, ‘Well then, what have you got planned for the rest of the day?’

I’m doing laps in a vat of salicylic acid. ‘Um … nothing really.’

‘Good idea. Take your time now, don’t rush.’ Dee handed me a pink terry robe and then l

eft the room.

In ten seconds flat, I’d donned the robe, grabbed my clothes and thongs, took five sizeable strides to get to the door, and ripped it open with such force, it didn’t have time to squeak. I lunged into the passage and nearly bowled Dee over. She looked like a Dee caught in headlights—‘Ooh’—but she quickly collected herself.

‘How are you feeling now?’

‘Er, like I could easily go to sleep.’ You have no idea how much fear can drain you.

She smiled smugly like as if her massage had had such a soothing effect: ‘It would be a good idea for you to have a warm shower now.’

No shit.

‘Or maybe hop into the spa.’

Oh yes, let’s spread the joy! ‘Good idea.’

‘See you again,’ she waved.

Uh-huh, let’s do lunch sometime. But not unless you get that wart cauterised!

I bolted for the bathroom.

The water cascading over my body was very hot. Hotter than your average frog could bear. I wasn’t about to jump out, though. I needed to reduce the viability of a potential virus. I scrubbed with a face cloth and used up half a little cake of hotel soap. It smelled like vanilla, but under the circumstances, who cared? I circled my stomach, then my chest, left shoulder, arm, palm, one finger, then another, and then ... what the fuck is that? A small, unfamiliar lump on pointer, left hand. Could it be?

Nooooooooooo!

I was screwed. With a separation in geography and time—two states and eighteen years since I last touched Dieter Baumschlager’s cursed fingers, he had finally got to mine ... through Dee. The wart himself was probably now wartless. The metallic taste of fear rose in my mouth. So many questions: was this a sign—one of the divine trumpetings before my personal doomsday (plague, maybe)? Did this mean that God was not chilling out on this Sunday? Did I have reason to fear my birthdays that fell on a Sunday? Was Dee Dieter’s sister?

Odyssey In A Teacup

Odyssey In A Teacup