- Home

- Paula Houseman

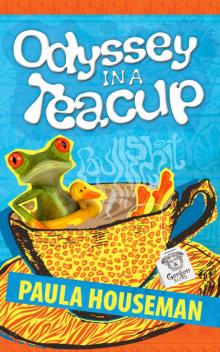

Odyssey In A Teacup Page 8

Odyssey In A Teacup Read online

Page 8

Miss Parker had a very gummy smile that exposed exceptionally long cuspids—the longest and yellowest I’ve ever seen on any human being. Her fingers were also yellow from too many cigarettes. In spite of this, she was so proper and schoolmarmish that I didn’t think she actually had a first name. And if she did, it was probably ‘Miss’. But neatly printed on her roll-call sheet was ‘Miss K. Parker’. The girls in the class thought ‘K’ stood for Kathleen. The boys thought it stood for Kunt.

Kathleen (or Kunt) wore twin sets and looked like she applied her face makeup with a trowel. In hindsight, I believe she may have been a drag queen, although she said, ‘I’m a thespian, not an actress.’ No one actually knew what the difference was, but a thespian sounded more important. Anyhow, we had to do more play-acting in her class than in any other English class in the school years after. It seemed, though, that thespians were serious people with no sense of humour. Once, when Miss Parker asked me a question, I smiled at her with my false, candy teeth in place. Everyone except Miss Parker thought it was funny. I think she was sensitive about the state of her teeth and might have thought I was making fun of her, which I was.

‘Quite the clown aren’t we, Miss Roth?’

‘I was just play-acting.’ The class laughed again.

‘Come here! And bring your writing exercise book with you!’ she boomed.

When I got to her desk, she grabbed the book out of my hand and wrote something on the first line of a fresh page, handed it back and said, ‘You can stay back after school. And you’re to write this two hundred times.’

I looked in my book and saw she’d written, ‘I must not be stupid and disruptive in class.’ I started to laugh.

‘And what is so funny now, miss?’

‘You’ve written that you must not be stupid and disruptive in class.’

The class erupted.

She slammed her hand on the desk and yelled, ‘YOU CAN WRITE IT FOUR HUNDRED TIMES!’

These days, restating something over and over is called a mantra. In those days, repeatedly writing lines was called an imposition. Either way, if you want something to change, you have to really feel and mean what you’re writing or saying. I invested no feeling in these lines so nothing changed. I remained stupid and disruptive, apparently, because I kept getting impositions that said so. I felt right at home in Miss Parker’s class. I probably filled several chapters in her bad books, although I never flashed my candy ivories at her again.

Sweets remained my opiate. Then again, so did savoury ... which pretty much covers all food. But the girls in my class didn’t understand my relationship with food any more than I understood theirs. The disparity became apparent in Home Science around the same time as the teeth incident (my second year of high school was not a good one).

Back then, Home Science was exclusively for girls, and it didn’t take long to realise that we were being groomed to eventually become Stepford wives. This didn’t sit well with someone like me. The other girls were kind of WASPish (snooty White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) and seemed happy to fly in formation, while I tended to fly in the face of convention. And the gossip in the schoolyard after the lesson in the third week of that term made it sound like I had walked on the wild side!

We were finally getting into the practical stuff and learning how to cook (after we’d learned to sew, knit and iron). At this lesson, we had to grill a lamb cutlet, and boil a small potato, a carrot, and a handful of fresh peas. Wow. Talk about underwhelming. This was neither the kind nor the quantity of food Sylvia dished up at home, but who cared? I was going to eat what I made. And I tucked into it with gusto. As the other girls in the class were struggling to get through their meal, I polished off everything on my plate, picked up the bone with my fingers to gnaw at any remnants on it, licked my fingers, wiped my hands on a cloth napkin, then put my hand up.

‘Yes, Ruth,’ said Miss Foley.

‘Can I please have some more?’

An audible, collective gasp filled the room. Conversation ground to a halt. The clattering of cutlery stopped. Everyone turned to look at me. Shit.

‘You pig,’ said nobody, but it was telepathically transmitted by everybody. I felt it keenly (I now understood Oliver Twist’s shame). These girls just did not get it. They weren’t Jewish, so how could they?

I felt so traumatised, I borrowed enough money from Maria to get myself a buttered finger bun just after the lesson when the rest of the school had lunch. The other girls sat in the lunch shed moaning about how bloated they were, and whispering to each other while they stared at me like I was from Nix. Named after Nyx, the goddess of darkness and night, it’s a moon that orbits Pluto. So what if it had yet to be discovered. The point was, it was still there, and the way these girls looked at me made me feel like nothing.

The following week at a parent teacher evening at the school, Miss Foley mentioned the incident to Sylvia, who then started to limit my after school snacks. Even though I was slim, I had a bit of a tummy. I didn’t really notice it until the mirror pointed it out just after Sylvia terrorised me with her cautionary advice. ‘If you don’t watch your weight now, you could end up fat. Like Zelda. It’s in the genes. You won’t be able to wear nice clothes and boys won’t ask you out.’ I was never encouraged to be fruitful the way Myron was; now I was going to be breadless and cakeless! But that wasn’t the worst of it. I called Ralph in a panicked state.

‘Different lineage,’ he’d said. ‘Zelda inherited her obesity-promoting gene from Aunt Miri. She’s not blood-related; she’s our aunt by marriage.’

Phew! Or, maybe not. ‘But then, I could end up fat like Sylvia.’

‘Sylvia’s not fat. Have you forgotten? She’s “fleshy”.’

We had both laughed. Even so, I’d been a little unnerved.

‘What she said’s disturbing me. Telling me I could end up fat, well, that targets my Achilles heel. Saying “like Zelda”; that’s Achilles himself. We learned about him in Mr Kosta’s lesson. He was one sick puppy ... I wanna kill myself!’

‘Ruthie, you could never be like Zelda. Sylvia’s just trying to bring you into line. She’s trying to Stepfordise you—make you believe that appearances are everything.’

In spite of myself and in spite of Ralph’s warning, Sylvia had succeeded to a point. My cacomorphobia had sprung up and I could no longer really enjoy the one thing I’d found comfort in, without being harassed by Sylvia and the mirror.

Now, lying in bed reflecting on the time between my second year of high school and the night before, at Zelda’s wedding, I was disturbingly aware that nothing had been off limits to Sylvia: my appetite, appearance, friendships, relationships, sexuality, opinions—everything was a potential target and means of controlling me. Having Ralph, Maxi and Vette in my life was a boon. And although I was spending as little time at home as I could once I’d got my licence and started working, I still slept there.

CHAPTER SEVEN:

LIGHTS ON, NOBODY HOME

The bogeyman comes out at night while you’re sleeping. In my nightmares, this mythical creature was fleshed out in female form, ambushing me and casting her spell over me while my defences were asleep. And the longer I stayed under Sylvia’s roof, the more spellbound I became. So, that defining moment at Zelda’s wedding was losing definition, and my bursts of confidence were ephemeral. Now you see me; now you don’t. Several months on, Ralph was worried about me.

‘Ruthie, you’re in danger of disappearing.’

I sighed. ‘I feel like I already have.’

‘Then you need to be resuscitated.’

‘Resuscitated? Uh ... don’t you mean “resurrected”?’

‘No. You’re unconscious, not dead and buried. You don’t need to come back in a new body, you just need to breathe life into your existing one. Your spirit’s drowning.’

Ralph had discovered New Ageism. And, as many newbies do when they first adopt an exciting practice, he tried to recruit me. I wasn’t interested, but what he said now was ri

ght. And you can’t usually see this sort of thing happening, especially when it’s by small degrees. Or in low ones, like in the boiling frog story. Throw froggy in boiling water, he’ll jump out. But put him in cold water and let it simmer slowly, he won’t notice it heating up. Then poof! You end up with a drowned, poached grenouille, whose skinny little legs will be sautéed, deep-fried, baked or grilled, and served up with a parsley butter sauce.

I was vacillating between hard-boiled and soggy, and in dire need of help. Ralph offered it.

‘There’s a meditation intro night on Sunday. It’s at the community hall near my place. You have to come,’ he implored. ‘It’ll do you good.’

Because of the way I was feeling, I figured it couldn’t hurt. Vette was interested and agreed to come along. She was curious; she hadn’t ended up becoming a Jubu and she wanted to see what spirituality that didn’t involve organised religion looked like. But Maxi was resistant.

‘What for? I’m already a flower child.’

‘Were,’ Ralph corrected.

‘What do you mean “were”?’

‘I deflowered you. Have you forgotten?’

She groaned. ‘God knows I am trying to!’

Ralph looked wounded, but he asked for that one. Maxi decided to join us, mostly just to humour us.

By Friday, I was actually looking forward to it, maybe because I had a hidden agenda. It was being held on a Sunday; I wanted to see if God Almighty would turn up.

I had an uneasy relationship with God. Feisty and wilful child that I’d been, Sylvia had often told me God would punish me. But she never gave me a specific date when this would go down, or the specific form the punishment would take. Because I was a ‘mistake’, it just had to happen. And I believed it would be momentous, so I had become increasingly vigilant. As my spirit became more submerged, the fear of God’s wrath started to gain on me. And a whole lot of things had conspired to convince me that my ruination would fall on a Sunday.

The first two weeks of a short stint at Sunday school when I was ten elaborated on what I’d learned about ‘Him’ from my parents. I was informed that He created the world in six days, and that because He was knackered after this, He called time out on day seven—Saturday (the Sabbath). But I believed God’s downtime was on Sunday—zzzz—and like the rest of us, His working week started on Monday. Even as a ten-year-old, this was a moot point for me, and I used to argue it with Gerard, my Sunday school teacher.

In his late twenties, Gerard was a cold, objectionable dogmatist. Tall and skinny, he had lacklustre grey eyes and a bad comb-over that pointlessly tried to hide his prematurely balding head. His wan complexion suggested he needed to spend more time in the sun instead of acting as if he was it. Like me, Gerard was stubborn. He would not budge on this particular issue, but nor would I, so I became his bugbear and spent every lesson thereafter outside the classroom for being ‘impudent and intractable’. According to Gerard, who the hell did I think I was to question the scriptures! Gerard acted like God’s proxy giving me a sneak peek at purgatory.

Despite my position about the hours God kept, I was confused about His identity. Sylvia often dovetailed her warnings that He would throw the book at me for being naughty, with the threat ‘Just wait till your father gets home!’ So, with a child’s logic, I concluded that Joe was God (he taught me to pray when I was five, but he didn’t actually say ‘You must pray to me’). Sylvia reinforced my assumption because she habitually called Joe a ‘know-all’, and I had learned that God was omniscient. I also learned that God was pure and perfect, and Sylvia implied that Joe was pure and perfect: ‘Oeuf! Tu crois que ta merde ne pue pas!’ (‘Egg! You think your shit doesn’t stink!’). Also, Joe was often emotionally absent, so I came to believe that God was not always omnipresent. He was never available on Sundays—not at Sunday school, not at home. Nowhere.

Every Saturday after work, Joe brought home two papers: The Advertiser, which was a broadsheet, and The News, a tabloid. Joe was more into populist trash than anything of political or social interest, so he favoured The News (he only bought The Advertiser to check out the car ads he’d placed in it). He also liked The Sunday Mail, another tabloid, which was delivered early Sunday mornings. On this day, when Sylvia launched her broadsides, Joe grabbed the broadsheet—Saturday’s Advertiser—and put it up in front of him as a kind of shield (twice the size of a tabloid, it covered most of his upper body). But it and he did nothing to shield me, so I understood that, like Joe, God didn’t protect.

Still, with a child’s trust, I prayed every night. But over time, on Sundays, my prayers began (and ended) with Yoo-hoo, are you there? On Sundays in my world, all hell broke loose. The diabolical extended family Sunday ritual was more evidence of God’s absence (being subjected to Sylvia daily was egregious; being subjected to Sylvia plus Zelda was more than flesh and blood could stand). But one specific incident that occurred a couple of months after I started Sunday school turned my assumptions about God’s Sunday absenteeism into a godforsaken, cold, hard fact.

Once in a while when the relatives didn’t get together on a Sunday, Joe and Sylvia took us driving.

‘Let’s go ta-tas,’ he would say.

Stuff that! Ta-tas was agony for Myron and me—we were not good travellers and both suffered car sickness. Add the foul stench of vanilla car deodoriser, plus the excruciating practice of window-shopping in the days when shops were closed on Sundays, by day’s end, Myron and I were a mess. Going from A to B was one thing: a purposeful journey, a means to an end. But Sunday drives were eternal damnation. Compounding our torment, we were forced to listen to 5DN—the old people’s radio station—and whatever crooner was filling the airwaves. Sylvia would hum along to the strains of Sinatra and the like—‘tee-ra-la-la-la’.

And so it was that one warm, windy Sunday, our parents decided a drive around the foothills would be nice. The car zigged and zagged on a winding road, Perry Como was warbling in the background, and Myron and I were gagging in the backseat. I wound my window down, but it didn’t help much.

Joe himself was a good traveller, but he had hayfever. He suffered from severe post-nasal drip and would often need to clear his throat. He didn’t spit the contents into a hanky, though. No. Not him. He spat in the garden, down the kitchen sink, on the footpath. And he didn’t care who was around at the time. Sylvia was never impressed.

‘Oeuf! C'est dégoûtant! Tu dois cracher partout?’ (‘Egg! It’s disgusting! Do you have to spit everywhere?’).

Go Mum!

‘You always spit over your shoulder!’

Go Dad! I laughed; she gave me a dirty look. And she didn’t have to strain to do it. Today, I was sitting behind him, not behind her, as I normally did. We were now cruising along a straight stretch of road, there was a temporary lull before the next nauseating song, and then ... it happened. There was that pig-like sound—a guttural back-snort, there was the rapid seesawing motion of Joe’s shoulders as he quickly unwound his window and then, there was the discharge. He spat a generous wad of phlegm into the troposphere.

But just at that precise moment, the wind changed direction (of course it did), picked up the airborne phlegm wad, and returned it through my open window at twenty-five knots. Splat. I heard it before the sensation registered on my right cheek. I retched. This was enough to get Myron going because he has a very sensitive gag reflex. He vomited all over his shorts, his legs, and onto the car seat. Just as well this happened in the days when car upholstery was mostly vinyl, not cloth, otherwise it would have been a bitch to clean and to remove the smell. The memory of this experience was imprinted on my cheek and my psyche, and it became encoded in my cells.

So I feared and hated Sundays, and wind, and I wasn’t too crazy about God either.

After this episode, I refused to suffer Gerard anymore—this scripture-stickler who had never endured Sunday drives, had never suffered the fetid odour of vanilla car deodoriser, had never worn Sunday phlegm wads on his cheek, and had never window

-shopped on a day when the whole bloody city shuts down! Well, Gerard could pontificate all he wanted. But Sunday must be God’s day of rest, not Saturday, because on Sundays, God was just not there to foil my parents’ satanic practices! And if I was going to Hell when I died, without question, I would be doomed to an eternity of Sundays in an infernal wind tunnel. Nope. I didn’t trust God.

Even so, I was prepared to give Him the benefit of the doubt on this Sunday meditation night.

Maxi, Vette and I waited for Ralph on the footpath outside the hall. He turned up five minutes after us. He was sporting a pair of black-rimmed glasses. It threw me.

‘Are those new? Why aren’t you wearing your contacts?’

‘I am wearing them. The glasses are fake.’ He put his finger where the lens should be and touched his eyelid. ‘I wanted to look intelligent.’

What an idiot.

‘Well you’ve already failed,’ said Maxi. ‘Chicks dig guys with scars, dumbo, not guys with glasses.’

Ralph whipped the frames off without a word, folded them carefully and put them in his shirt pocket.

The doors then opened and we started to file in. Finding God cost us a three dollars fifty entry fee.

‘Jesus, Ralph! We only used to pay twenty cents to get into a disco and it wasn’t all that long ago!’ I wasn’t happy. I was surprised, though. Big spending went against Ralph’s grain. Schooled in fiscal hardship, he was as tight as a fish’s arse.

‘Yes, but what benefits did you get from that in the long term?’

‘Laid!’ Maxi yawped.

‘Well then ... this could nourish your roots in a way you’ve never imagined.’

Ralph double lifted his eyebrows, we rolled our eyes, and he led us to the front of the hall. He decided we should sit in the very first row.

We took our seats, Ralph directly aligning himself with the microphone on the stage and within spitting distance of it. I sat on his right, Maxi was on his left and Vette was next to her.

Odyssey In A Teacup

Odyssey In A Teacup